In Project Management, if one thing is for sure, it’s that nothing is certain. You can try to plan everything to a ‘T’ and account for every possibility, but there will invariably be things that pop up unexpectedly. Sometimes this leads to project managers thinking, “If only I held more planning meetings and spent more time talking things over with my guys, then their best laid plans wouldn’t go awry“. Instead of looking back at the project planning as the issue, we can perhaps learn more by better understanding the nature of uncertainty itself. Uncertainty is a very important topic in quantum physics and understanding the nature of the universe. Since Scrum already uses some physics terminology, like velocities and projected values, I thought it would be fun to run with this idea and take some of the implications of quantum physics and see how they would translate if applied to project management.

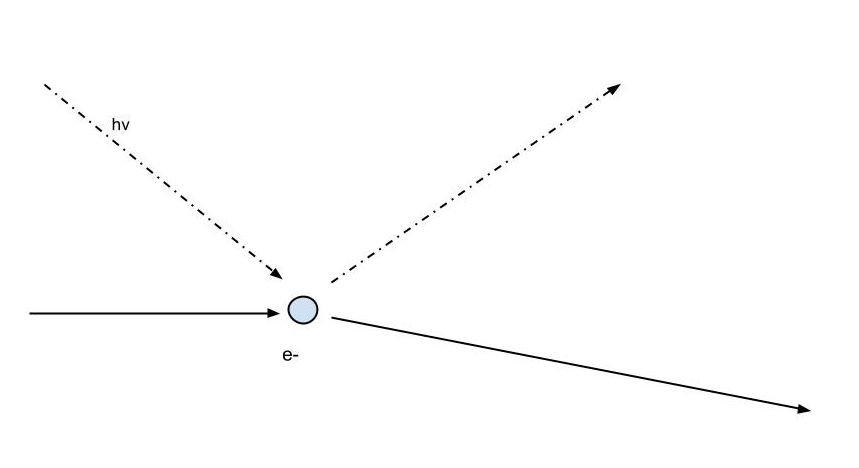

Before Breaking Bad brought him back, most of us remembered Werner Heisenberg for his uncertainty principle from high school physics. Mostly that you can you can never fully know the position and momentum of a particle at any given time. This is often misused or confused with the ‘Observer Principle’ meaning that you can’t measure something without actually affecting its outcome. For example if you have an electron traveling in space, the only way that you would be able to detect it would be by having it react with some other particle or detector that would then relay that information back to you.

In order to detect an electron to tell us where it is, we have to transfer or absorb some momentum from the electron, thus changing its momentum. It’s like if you have an overbearing manager demanding constant status updates. Just by getting a status update (taking a measurement to get the team’s position), he or she is consequently affecting the team’s momentum.

So what does the observer effect have to do with uncertainty? Nothing, really, but it’s often misrepresented as a result from uncertainty, so I thought I would address it first. This principle also has common classical examples, like how you can never accurately take your temperature using a mercury thermometer. Because the heat from your mouth flows into the thermometer and slightly cools your body, you can never get a truly accurate measurement.

Heisenberg’s actual uncertainty principle is represented by the formula:

Δx · Δp ≥ ℏ/2

Where Δx is the uncertainty of position, Δp is uncertainty of the momentum, and ħ is Plank’s constant over 2π. If either of these values were completely knowable, then the right side of the inequality would be 0, rather a constant! The fact that it is a positive number means the more you know about an object’s position, the less you can know about its momentum. Granted ℏ is an extremely small value (~1 × 10−34 J·s !), but the more you are checking up on a team’s progress there comes a point where you’re not learning anything new and are just affecting their momentum.

A lesser known relationship (and one that also has implications in Scrum) is:

ΔE · Δt ≥ ℏ/2

Notice that it has the exact same form as the previous equation. That’s because these are conjugate variables and also have to abide by the limit of uncertainty. Just as there is an inverse relationship between the uncertainty of position and momentum, there is a similar relationship between energy and time. The more you know about how much work is required for a particular task, the less you know about the time it takes to complete the task.

Many Scrum teams already account for this by using Story Points for estimates rather than using hours. Story Points removes the rigid constraint of estimating work in hours, and instead allows estimates based on similar user stories you’ve done in the past. I’m not saying that one method is better than the other, or would be the best for your team, but you’re not constrained by cosmic forces like uncertainty.

Since Scrum is an iterative process, you can have great success by focusing on things that you can say with a fair degree of confidence, while still allowing for some uncertainty in all planning and estimates.